In the new year, fitness pros often see their facilities and schedules inundated with people looking to make a change. In the right conditions, and under proper supervision, a resolutioner really can shift the direction of their life. But under the wrong conditions, inexperienced (and even experienced) exercisers, athletes and recreational enthusiasts can get into serious trouble, especially if they’re overly motivated and willing to just “push through.”

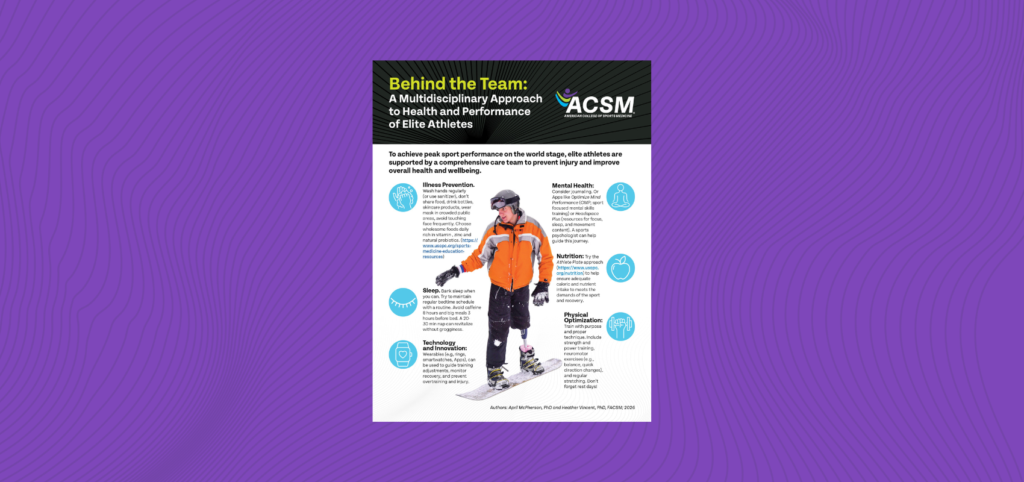

Beyond the routine ways a novice can injure themselves, starting a new sport or fitness routine in the winter presents further complications. Cold can significantly affect performance, and according to the 2021 “ACSM Expert Consensus Statement: Injury Prevention and Exercise Performance during Cold-Weather Exercise,” “cold is a leading cause of death among people engaged in sports.”

Depending on the facility you work at and the nature of sport or activity you supervise, cold can be anything from an inconvenience to a serious danger. Let’s start this discussion with the way cold hampers our ability to exercise and perform, then move on to the ways it can actively harm us.

Exercise performance

According to the consensus statement authors, cooler muscle temperatures lower not only the amount of time we’re able to exercise but also power and even VO2max, though most of these effects seem to be related to explosive or anaerobic exercise. A 1° C (~0.6° F) drop in muscle temperature can equate to a 4-6% decrease in these categories. An 8° C (14.4° F) drop can draw down muscles’ power output by 31% (though if the temperature of your muscles has fallen that far, exercise performance would probably be the last thing on your mind). Low muscle temperatures lead to higher levels of lactate in muscle tissue, and exercising in colder temperatures increases the amount of lactate in the blood relative to exercising in warmer temperatures.

Whether cold temperatures impact aerobic exercise in the way they do more explosive activities is up for debate. The consensus statement authors note that studies have reported results ranging from cold temps decreasing aerobic performance to actually increasing performance (or having no effect at all). And the extent to which insulated clothing may improve performance by keeping us warm versus impede performance by being bulky, heavy or ungainly is also an open question.

However, when it comes to injury, we have a little more information to work with. Let’s consider three common cold-weather dangers: frostbite, nonfreezing cold injury, and hypothermia.

Frostbite

Simply put, frostbite occurs when tissue freezes. The small ice crystals that form within the tissue physically damage the cells; then, thawing the area leads to reperfusion injury and inflammation.

Depending on outside conditions, frostbite can arise from a long period of exposure or in only seconds. It’s more likely to occur with increasing wind chill or if your skin has gotten wet, since evaporation leads to rapid cooling. Touching a cold material, like a metal streetlamp or fence, can also lead to frostbite via contact cooling. And in salt water, tissue may freeze at – 0.55°C / 31°F, even though the salt water itself will not freeze until it hits −1.9°C / 28.6°F.

Frostbite is also more likely to occur in areas of the body that are exposed to the elements and/or tend to receive less blood flow, like the hands, feet and head. Men seem to be more likely to get frostbite, though this might be due to sociological rather than physical differences between the sexes. Children and the elderly are also more affected, as are people of African ancestry. People with diabetes or multiple sclerosis may also be more susceptible.

As noted by the consensus statement authors, there are four degrees of frostbite, each with particular physical findings.

- First degree frostbite will present with numbness, and the central part of the affected area will be a waxy white or yellow color while the surrounding tissue will be red, swollen, and flakey or peeling. The surrounding tissue will itch or burn.

- In second degree frostbite, the central portion of the skin will develop surface blisters and the surrounding area will be red and swollen.

- Third degree frostbite mimicks the signs of second degree frostbite, but blood blisters form with 24 hours and the entire thinckness of the affected skin will be lost.

- In fourth degree frostbite, the damage includes not only all of the skin in the affected area but also extends into the tissue below, including muscle and bone.

Some ways to avoid frostbite include keeping an eye on the wind chill, keeping extremities covered and maintaining your core temperature. Frostbite is serious, so if you suspect you or a client may have developed it, it is important to seek medical attention.

Nonfreezing Cold Injury

Nonfreezing cold injury (NFCI) differs from frostbite in that, as the name suggests, the affected area doesn’t actually freeze. Typically occurring in cool and wet conditions, such injuries usually take a significant amount of time to develop. NCFI can begin to set in when the temperature of the tissue itself falls below 15°C / 59°F for an extended period, usually over the course of a number of days or even weeks — i.e., more likely on a backpacking trip or during military training than while pursuing discrete bouts of regular exercise. However, that isn’t always the case. NFCI can occur in less than a day depending on the individual affected and the conditions involved, and a mild form, chilblains, can form within one to five hours. A key factor in the development of NFCI during these shorter exposures is whether the tissue is adequately rewarmed.

Like frostbite, NFCI is more likely to occur in the extremities. Depending on severity, the aftereffects may last a matter of days to months. Significant damage can lead to symptoms lasting years, from pain and neuropathy to cold sensitivity and excess sweating.

Water can play a major role in the onset of NFCI. In nonfreezing temperatures, contact with water can increase cooling by directly conducting heat away from the body during submersion or via evaporation afterward. Consequently, waterproof boots, as well as gloves that can breathe to release moisture built up during activity, may help mitigate the risk of NFCI in certain conditions.

Hypothermia

Hypothermia occurs when core body temperature drops below 35° C / 95° F, meaning your body is losing heat faster than it can produce it. Exercise increases heat production, so staying moving is important, but so is wearing appropriate clothing. The authors describe a breathable base layer that wicks moisture away from the skin, an insulating layer, and an outer layer that protects from wind and water but allows moisture to escape via vents or other openings. Of importance, though, they note:

“The outer layer should typically not be worn during exercise (unless it is raining or very windy) but should be donned during subsequent rest periods. … A common problem is that people begin exercising while still wearing clothing layers appropriate for resting conditions, and thus are ‘overdressed’ after initiating exercise.”

If you’re overdressed, the excess moisture you build up in your clothing during exercise can then increase the rate of cooling you experience once you’re finished exercising.

Also of note, low blood sugar can prevent you from shivering. Since this is an important way to maintain body temperature as conditions get colder, make sure your body is adequately fueled.

Hypothermia can be divided into three categories. The first is “mild,” during which time the body’s core temperature ranges from 32 to 35° C / 89.6 to 95° F. According to the authors, signs and symptoms at this stage include “cold extremities, shivering, tachycardia, tachypnea, urinary urgency (and) mild incoordination.” (“Tachypnea” is abnormally quick breathing.)

The second category, “moderate” arises at body temperatures ranging from 28 to 31° C / 82.4 to 88° F. Those experiencing moderate hypothermia may exhibit “apathy, poor judgement, reduced shivering, weakness and drowsiness, slurred speech and amnesia, dehydration, decreased coordination or clumsiness (and) fatigue.”

The third category, “severe” sets in at core temperatures below 28° C / 82.4° F. Signs include “inappropriate behavior, total loss of shivering, cardiac arrhythmias, pulmonary edema, hypotension and bradycardia, reduced level of consciousness (and) muscle rigidity.” (“Bradycardia” is a slower-than-normal heart rate.)

As the body cools further, the affected person will lose consciousness. Without intervention, they will die.

The consensus authors recommend different courses of action depending on the stage and condition of the hypothermic individual. When out in the field, those with mild hypothermia and no other conditions should be given warm clothing and sugary drinks, encouraged to actively rewarm themselves, and be monitored.

Further, the authors write “In mild hypothermia cases that recover fully and risk factors are mitigated, there is no need to evacuate.” (Meaning the affected person doesn’t need to be brought to a medical facility.)

However, they continue: “For moderate and severe hypothermia and the critically ill, patients need to be handled very gently (as mechanical impact can trigger cardiac arrest), kept insulated, passively rewarmed slowly (0.75 to 1.0°C·h−1) and evacuated.”

In sum

Cold weather presents its own unique set of obstacles and dangers, and it’s important to take into account the conditions that you and/or your clients will be exercising, performing or competing in — not only the ambient temperature but also windchill, dampness and the likelihood you’ll encounter standing water. Wearing the proper clothing and protective gear is important, as well as knowing the right amount of layers to wear when exercising vs. when resting. Proper precautions can go a long way to preventing injury and tragedy.

However, this piece is just an introductory blog post; if you are likely to face any of the conditions outlined above, I highly recommend reading “ACSM Expert Consensus Statement: Injury Prevention and Exercise Performance during Cold-Weather Exercise” and, more importantly, seeking out reliable continuing education and professional training. It never hurts to be prepared.