by

Greg Margason

| Aug 29, 2023

Over the last decade or so, assessing static and dynamic posture has become increasingly common during health and fitness assessments performed by certified fitness professionals with clients, athletes, and patients. This has been a great addition to certified fitness professionals’ toolboxes to assist in determining possible postural deviations and movement compensations that may be caused by muscular imbalances. These muscular imbalances may then be corrected through exercise performed with a certified fitness professional before they lead to either acute and/or chronic musculoskeletal conditions and pain. ACSM has recently introduced a static posture assessment via a plumb line in ACSM's Resources for the Exercise Physiologist: A Practical Guide for the Health Fitness Professional (3rd ed.).

Over the last decade or so, assessing static and dynamic posture has become increasingly common during health and fitness assessments performed by certified fitness professionals with clients, athletes, and patients. This has been a great addition to certified fitness professionals’ toolboxes to assist in determining possible postural deviations and movement compensations that may be caused by muscular imbalances. These muscular imbalances may then be corrected through exercise performed with a certified fitness professional before they lead to either acute and/or chronic musculoskeletal conditions and pain. ACSM has recently introduced a static posture assessment via a plumb line in ACSM's Resources for the Exercise Physiologist: A Practical Guide for the Health Fitness Professional (3rd ed.).

For the scope of this article series, we will simply be discussing how to perform a static postural assessment. However, there are some great resources available that can assist the certified fitness professional in assessing the movement of clients, athletes, and patients via dynamic assessments such as the overhead squat; single-leg squat; split-squat; gait analysis; jumping and landing; and upper-body pushing, pulling, and pressing. All of these are great follow-ups to confirm possible findings from the static postural assessment and lead to further single-joint mobility assessments to confirm any possible joint mobility issues.

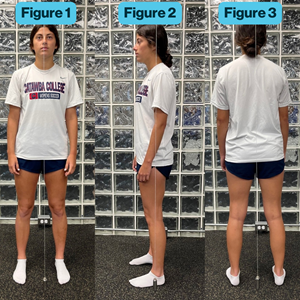

When assessing static posture, the certified fitness professional will assess the client from both the anterior (Figure 1) and lateral (i.e., sagittal) view (Figure 2). Assessing the client from the posterior view (Figure 3) may be beneficial to confirm possible findings from the anterior view (specifically at the foot/ankle region) but will not be discussed in this article. Please note that this article will be assessing specific areas of the body from each view in an attempt to witness the three most common postural distortion syndromes: (a) pes planus/pronation distortion syndrome, (b) lower crossed syndrome, and (c) upper crossed syndrome.

When assessing static posture, the certified fitness professional will assess the client from both the anterior (Figure 1) and lateral (i.e., sagittal) view (Figure 2). Assessing the client from the posterior view (Figure 3) may be beneficial to confirm possible findings from the anterior view (specifically at the foot/ankle region) but will not be discussed in this article. Please note that this article will be assessing specific areas of the body from each view in an attempt to witness the three most common postural distortion syndromes: (a) pes planus/pronation distortion syndrome, (b) lower crossed syndrome, and (c) upper crossed syndrome.

When assessing static posture, certified fitness professionals may use a plumb line to assist in witnessing possible postural deviations and/or asymmetries. However, a plumb line is not required. To learn how to hang a plumb line appropriately, please see the section of this webpage titled “Assessment.” Certified fitness professionals may also use posture assessment grids or simply line the client up to a vertical line of a wall as a reference point.

Prior to assessing your client’s posture, please be sure that your client is wearing either shorts or yoga pants, a T-shirt or tank top, and has removed their footwear. Form-fitting clothing is preferred and will allow the certified fitness professional to more easily identify postural deviations. If a plumb line is used, the certified fitness professional should line the client up properly in both the anterior and lateral views, as well as the posterior view, if used. When assessing clients’ static posture, clients may become very self-conscious of their posture, which will affect the validity and reliability of the assessment. Therefore, the certified fitness professional should ask their client to stand naturally as if they were doing something like waiting for an elevator. The certified fitness professional may also ask the client to “shake everything out” prior to the assessment or even perform a few mini squats to allow the client to assume as natural a static posture as possible.

From the anterior view, the client should stand facing the plumb line (if used), with the plumb line or line in the wall halfway between the client’s feet. The plumb line should be aligned with the client’s pubis. From the anterior view, the certified fitness professional is specifically assessing the posture of the feet, ankles, knees, and hips. When viewing the client from the lateral view, the plumb bob at the bottom of the plumb line (if used), should line up just anteriorly to the client’s lateral malleolus. From the lateral view, the certified fitness professional is specifically assessing the posture of the hips, pelvis, lumbar spine, thoracic spine, shoulder complex (i.e., scapula and shoulder joint), neck, and head. Please note, further body areas may be assessed. However, for the scope of this article, only the body areas mentioned above will be assessed.

In the first part of this article series, we discussed the importance of certified fitness professionals performing static postural assessments with their clients, athletes, and patients. Within the second part of this article series, we will be describing the process of performing a static postural assessment, what an “ideal” static posture should look like, and common deviations from ideal posture that may indicate postural distortion syndromes such as pes planus/pronation distortion syndrome, lower crossed syndrome, and upper crossed syndrome.

Related content:

Blog | A Fitness Professional’s Introductory Guide to Assessing Static Posture: Part II

Related CEC Courses:

Using Posture to Enhance Movement (1 CEC)

Anatomy of Movement (5 CECs)

Ryan R. Fairall, Ph.D., ACSM-EP, EIM, CSCS,is an assistant professor of exercise science at Catawba College in Salisbury, N.C. He has worked in the fields of health/fitness and sports since the year 2000, has been a certified personal trainer since 2003, and has been an instructor in higher education since 2015. In his free time, Ryan enjoys being physically active — lifting weights, playing sports, kayaking, fishing, going on walks with his female Shih Tzu, Bledsoe, and watching his hometown Philadelphia sports teams, which can be very frustrating at times.