How does a healthy heart beat?

The human heart consists of four chambers and its own electrical system to pump blood throughout the body. At rest, the average heart pumps about five liters of blood per minute with an average resting heart rate of 80 beats per minute (bpm). However, with vigorous activity, heart rates can increase up to 200 beats per minute and pump up to 25 liters of blood per minute throughout our body.

The upper two chambers, the right and left atrium, passively receive blood. The right atrium receives blood that has already passed through the body, while the left atrium receives blood from the lungs that will now provide the oxygen our bodies need. Our heart also has the ability to generate an electrical signal or impulse. Each electrical impulse generates a heartbeat. The electrical signal starts in a small group of cells at the top of your heart called the sinoatrial (SA) node. This signal then spreads through your two atria to your two ventricles. In a healthy heart, the signal travels very quickly. This allows the muscles in the heart to contract in the correct sequence, assuring the heart works as efficiently as possible

What may change how my heart beats?

Many conditions may change how the human heart beats; one of these conditions is called atrial fibrillation (Afib). Afib is the most common arrhythmia with an estimated U.S. prevalence of 5.2 million people.

What is Afib?

Atrial fibrillation is a problem with your heart’s electrical signals. Afib causes the beating of your upper chambers (atria) to be irregular, making it difficult for the lower chambers (ventricles) to pump blood to the body. In Afib, the heart’s electrical impulses don’t begin in the SA node as is appropriate, but rather in other areas of the atria or in the nearby pulmonary veins. The abnormal impulses become rapid and chaotic, spreading through the atria in a disorganized manner. This causes the muscles of the atria to fibrillate, or quiver, rather than contract normally. This phenomenon results in a loss of atrial contribution to the pumping of blood, leading to a 10 to 30% decrease in blood volume to the ventricles prior to contraction. So instead of a potential five liters of blood leaving the ventricles per minute, it may be reduced to 3.5 to 4.5 liters per minute. The AV node becomes unable to conduct impulses from the atria as quickly as they arrive, resulting in the atria beating faster than the ventricles. During atrial fibrillation, the atria beat 400 to 600 times per minute, while the ventricles may beat up to 175 times per minute. The atria and ventricles, therefore, beat in an uncoordinated manner, creating a rapid and irregular heart rhythm.

What are the three types of Afib?

The types of Afib are based on how long the arrhythmia lasts. When first diagnosed, many individuals experience paroxysmal Afib, which is when the arrhythmia starts abruptly and stops on its own. The spontaneous ending of the arrhythmia occurs within seven days of its onset. When the arrhythmia does not stop on its own, it is called persistent Afib. Treatment may be required to return the heart back to a normal rhythm. When a normal heart rhythm cannot be reestablished with treatment, and no further efforts are made to restore the rhythm, it is referred to as permanent Afib. Both paroxysmal and persistent Afib may become more frequent and, over time, result in permanent Afib.

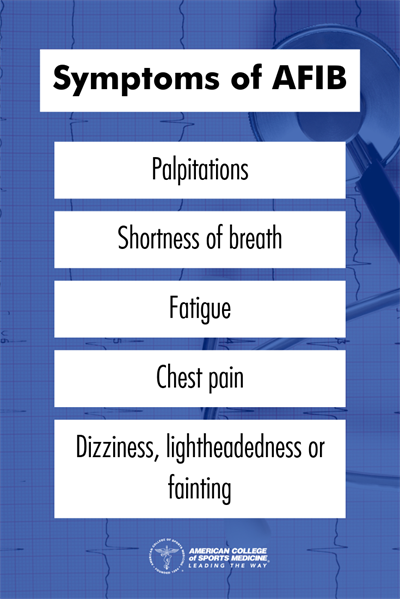

What are the symptoms of Afib?

- Palpitations

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea)

- Fatigue

- Chest pain

- Dizziness, lightheadedness or fainting (syncope)

However, between 25 and 35 % of individuals with Afib do not experience any symptoms.

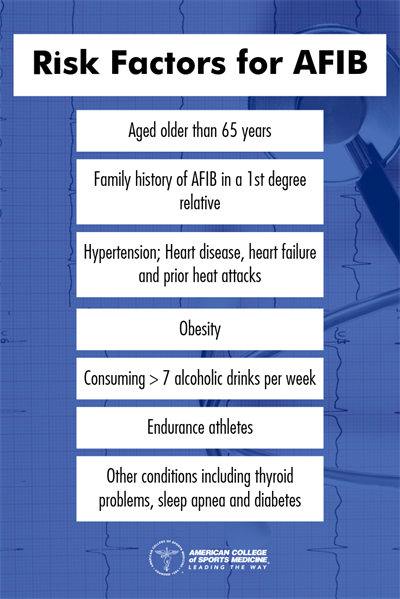

What are the risk factors for Afib?

Individuals who have one or more of the following are at an increased risk for Afib:

- Aged older than 65 years

- Family history of Afib in a first-degree relative

- Heart disease, including valve problems, heart failure and prior heart attacks

- Hypertension defined as systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥80 mmHg

- Obesity defined as a body mass index ≥30 kg/m2

- Alcohol consumption ≥7 standard drinks per week

- Endurance athletes

- Other chronic conditions, such as thyroid problems, sleep apnea and diabetes

Why is it important to treat Afib?

Afib can lead to other serious health problems including other heart arrhythmias, stroke and heart failure. The atria are unable to pump blood as effectively into the ventricles, causing blood to pool in the atria. This pooling of blood can lead to the formation of clots. If a clot travels from the heart through the bloodstream to the brain, it can block blood supply and cause a stroke. This is a serious concern as an individual with Afib is five times more likely to have a stroke compared to an individual with normal heart function. Afib could also lead to heart failure, which is the heart’s inability to pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs.

How is Afib treated?

Afib may be managed through medication or surgical intervention, and some patients might need cardioversion—a controlled electrical shock that requires anesthesia. In most cases, interventions using medication will be used first (about 80 to 90% of patients), and ablation will only be considered if treatment using medication is unsuccessful. The goal of medical management is to reduce heart rate and better control the rhythm. This allows the heart adequate filling time between contractions. Additional treatment options will be prescribed based on patient symptoms and risks of developing blood clots that travel through the body to potentially clog veins (thromboembolism) secondary to Afib.

What are interventions using medication?

Beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers are prescribed to lower the heart rate in Afib patients. The goal is to lower the resting heart rate to less than 100 beats per minute, because lowering the heart rate allows the heart to better fill and reduces symptoms. For patients presenting with an irregular heartbeat, rhythm controlling medications such as sodium channel blockers and potassium channel blockers may be used to restore and maintain a normal heart rhythm. However, these medications alone may not resolve the irregular rhythm.

As indicated, Afib increases an individual’s risk for blood clots in the heart. The blood clots form due to blood pooling in the atrium and lack of effective heart contraction. Blood clots may travel out of the heart and into the coronary vessels or other areas of the cardiovascular system, resulting in increased risk for heart attack or stroke. To prevent heart attack or stroke due to thromboembolism, a patient usually is prescribed anti-clotting medications including anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs.

When to use cardioversion?

Cardioversion is used to restore the regular heart rhythm. A physician may prescribe one of two forms of cardioversion. The first form is pharmacological cardioversion and may return your heart to normal sinus rhythm. Pharmacological cardioversion is used in patients with Afib onset less than 48 hours and who have low risk of cardiovascular disease. The second form, electrical cardioversion attempts to reset the sinus node and induce normal sinus rhythm. It is well recognized that cardioversion increases the risk of thromboembolism; thus, using anticoagulant medication is essential before and after cardioversion.

When to use ablation?

Patients who cannot tolerate the medications or if the medications are not effective may be recommended for cardiac ablation. Cardiac ablation reduces blood clot formation by 99.4% after the surgery. Surgical cardiac ablation, an invasive procedure, is only used in patients with complicated cardiac disease with Afib (less than 0.008 percent). Catheter ablation or pulmonary vein ablation is the least invasive type. In this procedure a thin, flexible tube is inserted into blood vessels in the groin, forearm or neck and guided to the heart. Physicians may use heat, cold or radiofrequency to inactivate irritable atrial tissue returning to regular heart rhythm. The decision of which type of ablation to use depends on the presence of symptoms, causes of Afib and the chance of having other heart diseases.

Is it safe to exercise with Afib?

Exercise is well known to be beneficial to overall health by increasing cardiopulmonary and skeletal muscle fitness. Increased cardiopulmonary fitness reduces known cardiac risk factors, which include hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia and obesity. Exercise has also been demonstrated to be safe in patients with Afib. Some sports that involve contact or have a high incidence of collision are not recommended for someone who is on anticoagulation medications due to the increased risk of bleeding. Studies demonstrate that an exercise prescription for Afib patients reduces the Afib burden, which can include fatigue, periods of lightheadedness, and reduce the total time spent in the arrhythmia. In addition to reduction of Afib episodes and symptoms, exercise provides patients with overall health benefits including improved quality of life.

Learn more about being active when you have Atrial Fibrillation from ACSM's Exercise is Medicine® initiative.

Download the Fact Sheet

Authors: Donna Cataldo, PhD, Clinical Professor: Kinesiology Program, Clinical Exercise Physiology MS Program Coordinator, Past President University Senate, Barrett Honors Faculty, Arizona State University; Houria Alabbas MS; Bobbie Trude, MS; Aubrey Smith, MS

References

Aehlert, B. (2018). ECGs made easy. Phoenix, AZ: Southwest EMS Education, Inc.

American Heart Association. (2017, Jan 9). How the healthy heart works? Retrieved from http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/CongenitalHeartDefects/AboutCongenitalHeartDefects/How-the-Healthy-Heart-Works_UCM_307016_Article.jsp#.WrGLLejwbid

American Heart Association. (2017, Jun 28). Atrial fibrillation medications. Retrieved from http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/Arrhythmia/AboutArrhythmia/Atrial-Fibrillation-Medications_UCM_423781_Article.jsp#.WrGLUOjwbi

Bosomworth, N. J. (2015). Atrial fibrillation and physical activity: Should we exercise caution? Canadian Family Physician, 61(12), 1061–1070. Retrieved from http://www.cfp.ca/content/61/12/1061

Camm, A., Kirchhof, P., Lip, G., Schotten, U., Savelieva, I., Ernst, S., . . . Zupan, I. (2010). Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. European Heart Journal, 31(19), 2369-2429. http://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euq350

Calkins, H., Hindricks, G., Cappato, R., Kim, Y., Saad, E. B., Aguinaga, L., & Kuck, K. H. (2018). 2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Europace. 20, e1–e160. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.joa.2017.08.001

Colilla, S., Crow, A., Petkun, W., Singer, D. E., Simon, T., & Liu, X. (2013). Estimates of current and future incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the U.S. adult population. The American Journal of Cardiology, 112(8), 1142-1147. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.05.0

Elliott, A. D., Mahajan, R., Pathak, R. K., Lau, D. H., & Sanders, P. (2016). Exercise training and atrial fibrillation: further evidence for the importance of lifestyle change. Circulation. 133(5), 457-459. http://doi.org10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020800

Gleason, K.T., Nazarian, S., & Dennison Himmelfarb, C. R. (2017). Atrial fibrillation symptoms and sex, race, and psychological distress: a literature review. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, Advance publication online. http://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0000000000000421

Iscan, S., Eygi, B., Besir, Y., Yurekli, I., Cakir, H., Yilik, L., . . . Gurbuz, A. (2018). Inflammation, atrial fibrillation and cardiac surgery; current medical and invasive approaches for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Current Pharmaceutical Design, Advance publication online. http://doi.org/10.2174/1381612824666180131120859

January, C. T., Wann, L. S., Alpert, J. S., Calkins, H., Cigarroa, J. E., Cleveland, J. C., . . . Yancy, C. W. (2014). 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation, 130(23), 2071-2104. http://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000040

Kirchhof, P., Benussi. S., Kotecha, D., Ahlsson, A., Atar, D., Casadei, B., & Vardas, P. (2016). 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Europace, 18, 1609–1678. http://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euw295

Klabunde, R. E. (2012). Cardiovascular physiology concepts. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Long, B., Robertson, J., Koyfman, A., Maliel, K., & Warix, J. R. (2018). Emergency medicine considerations in atrial fibrillation. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, Advance publication online. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.01.066

Lau, D. H., Nattel, S., Kalman, J. M., & Sanders, P. (2017). Modifiable Risk Factors and Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation, 136, 583–596. http://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023163.

Menezes, A. R., Lavie, C. J., De Schutter, A., Milania, R. V., O’Keefeb, J., DiNicolantoniob. J. J., & Abi-Samra, F. M. (2015). Lifestyle Modification in the Prevention and Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 58, 117-125. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2015.07.001.

Munshi, N. V. (2012). Gene regulatory networks in cardiac conduction system development. Circulation Research, 110(11), 1525-1537. http://doi.org/10.1161.CIRCRESAHA.111.260026

Malmo, V., Nes, B. M., Amundsen, B. H., Tjonna, A. E., Stoylen, A., Rossvoll, O., . . . Loennechen, J. P. (2016). Aerobic interval training reduces the burden of atrial fibrillation in the short term: a randomized trial. Circulation, 133(5), 466-473. http://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018220.

Narayan, S. M., Krummen, D. E., Shivkumar, K., Clopton, P., Rappel, W. J., & Miller, J. M. (2012). Treatment of atrial fibrillation by the ablation of localized sources: CONFIRM (Conventional Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation With or Without Focal Impulse and Rotor Modulation) Trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 60(7), 628-636. http://doi.org/10.1016.j.jacc.2012.05.022

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (n.d.). Atrial Fibrillation. Retrieved from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/atrial-fibrillation.

Staerk, L., Sherer, J. A., Ko, D. Benjamin, E. J., & Helm, R. H. (2017). Atrial fibrillation: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical outcomes. Circulation Research, 120, 1501-1517. http://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.309732

Shemin, R. J., Cox, J. L., Gillinov, A. M., Blackstone, E. H., & Bridges, C. R. (2007). Guidelines for reporting data and outcomes for the surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 83(3), 1225-1230. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.11.094

Voskoboinik, A., Prabhu, S., Ling, L., Kalman, J. M., & Kistler, P. M. (2016). Alcohol and atrial fibrillation: a sobering review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 68(23), 2567–2576. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.074

Zoni-Berisso, M., Lercari, F., Carazza, T., & Domenicucci, S. (2014). Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: European perspective. Clinical Epidemiology, 6, 213-220. http://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S47385