Jill Barnes, Ph.D., FACSM |

Feb.

22, 2019

In February, we often see many people wearing the color Red. Wearing Red may be a tribute to St. Valentine, but the color Red should also serve as a reminder to take care of our hearts, as February is Heart Disease Month! According to the Center of Disease Control and Prevention, heart disease accounts for one of every four deaths in the United States. Many of the causes of heart disease are well-known, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes and obesity. Fortunately, there are also well-known lifestyle and behavior changes that can drastically reduce the risk of heart disease and include: smoking cessation, eating a healthy diet and exercising.

Despite the multitude of data showing that lifestyle behaviors can reduce the risk of heart disease and improve cardiovascular health, the Framingham Offspring Study recently reported that the percentage of people with ideal cardiovascular health (using the American Heart Association’s definition of Ideal Cardiovascular Health) has declined over the past 20 years.

Even in the absence of heart disease, the increasing percentage of Americans with less than ideal cardiovascular health translates to greater risk of heart disease and increased all-cause mortality. Because the heart and cardiovascular system are vital factors in overall health, other organ systems will be affected by less-than-ideal cardiovascular health. Importantly, adults having an ideal cardiovascular health score during the middle-aged years had a lower risk of cognitive decline and dementia. In addition, large-scale epidemiological studies have continued to show a strong correlation between cardiovascular health and brain health.

What is the link between cardiovascular health and brain health?

It is possible that heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease or dementia have common risk factors and that is why there are correlations between these conditions. However, the brain requires a large amount of blood flow, which needs to be precisely controlled to maintain optimal neuronal function. If a patient has a problem with the function of the heart or blood vessels, this could prevent adequate blood flow supply to the brain and eventually affect brain function and cognition. We know that patients with congestive heart failure have higher incidence of dementia. In heart failure patients, a reduced capacity of the left ventricle to pump blood (i.e. ejection fraction) is associated with poor cognitive test scores.

The function of the large vessels supplying blood flow to the brain are also important to overall brain health. A paper published almost 70 years ago first reported that patients with carotid occlusion (due to atherosclerosis) eventually progressed to dementia. This early case study was the first to suggest that mild hypoperfusion of the brain, due to large vessel stenosis, could lead to dementia.

Dysfunction in the heart (or pump) or the large blood vessels (or conduits) is associated with reduced cognitive function, but the small blood vessels in the brain that control the blood supply to neurons may also contribute to the link between cardiovascular health and brain health. This hypothesis was first proposed decades ago, based on evidence of disrupted microvessel structure in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Disruption in the microvessels can lead to hypoperfusion, disrupt the blood-brain-barrier or reduce the ability of the brain to utilize glucose. Collectively, an interruption at any segment of the blood delivery system (heart, large and small blood vessels) could impair the ability of the brain to function optimally.

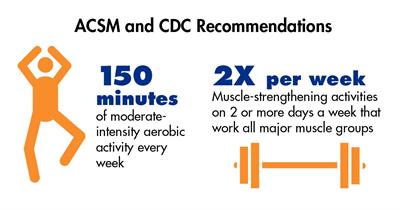

Now, for the good news: Because of the link between heart health and brain health, we know that lifestyle behaviors (like exercise!) can reduce the risk of developing heart disease AND developing cognitive decline. Older adults who are more physically active have better brain health compared with sedentary counterparts, suggesting a protective effect of exercise. And although more research is necessary to determine how exercise may promote healthy brain aging and what might be the optimal training program, using what we know about what works for heart health and following ACSM’s guidelines for physical activity is a great place to start.

Now, for the good news: Because of the link between heart health and brain health, we know that lifestyle behaviors (like exercise!) can reduce the risk of developing heart disease AND developing cognitive decline. Older adults who are more physically active have better brain health compared with sedentary counterparts, suggesting a protective effect of exercise. And although more research is necessary to determine how exercise may promote healthy brain aging and what might be the optimal training program, using what we know about what works for heart health and following ACSM’s guidelines for physical activity is a great place to start.

Perhaps wearing Red in February should be a reminder to take care of our heart so that our heart can take care of our brain.

Jill Barnes, Ph.D., FACSM, is an Assistant Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the Department of Kinesiology and has an affiliate faculty appointment in the Division of Geriatrics and Gerontology in the School of Medicine and Public Health.