Ryan R. Fairall, Ph.D., ACSM-EP, EIM, CSCS |

Sept.

22, 2023

In the first part of this blog series, we discussed the importance of performing a static postural assessment with your clients, athletes, and patients. This second article introduces the basic static postural assessment and demonstrates how to spot common postural deviations, likely driven by muscular imbalances, that may lead to acute and/or chronic musculoskeletal conditions and pain.

As stated in the first part of this series, the three most common postural distortion syndromes are a) pes planus/pronation distortion syndrome, b) lower crossed syndrome, and c) upper crossed syndrome. For the scope of this article, we will only cover how to assess clients’ static posture for these three postural distortion syndromes. However, fitness professionals should be aware that clients may exhibit other static postural deviations (e.g., kyphotic-lordotic posture, flat-back posture, sway-back posture, genu/knee varus or bowed legs, etc.).

When assessing clients’ static posture from the anterior and lateral views, fitness professionals can assess each of the body’s five kinetic chain checkpoints: foot/ankle, knees, lumbopelvic hip complex, shoulder complex, and head/neck. In this article, we will focus on assessing clients from the anterior view for signs of pes planus/pronation distortion syndrome and from the lateral view for signs of lower crossed syndrome and upper crossed syndrome.

Pes Planus/Pronation Distortion Syndrome

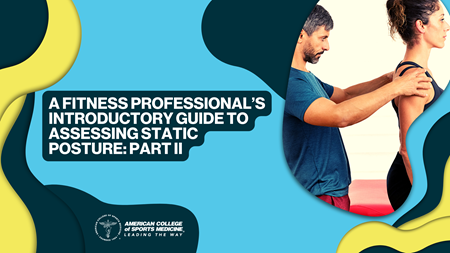

From the anterior view, have the client remove their shoes, then line them up to the plumb line (if available), a line on the wall, or an imaginary vertical line with their feet approximately shoulder width apart. The line should lie halfway between their feet and be aligned with their pubis (Figure 1). When assessing the foot, the toes should be pointed straight ahead and the feet should have a normal medial longitudinal arch (i.e., not too high of an arch and not too low of an arch or flat feet) (Figure 2). The client’s knees (i.e., patella) should be facing straight ahead, and the patella should be approximately in line with the client’s second or third toe.

From the anterior view, have the client remove their shoes, then line them up to the plumb line (if available), a line on the wall, or an imaginary vertical line with their feet approximately shoulder width apart. The line should lie halfway between their feet and be aligned with their pubis (Figure 1). When assessing the foot, the toes should be pointed straight ahead and the feet should have a normal medial longitudinal arch (i.e., not too high of an arch and not too low of an arch or flat feet) (Figure 2). The client’s knees (i.e., patella) should be facing straight ahead, and the patella should be approximately in line with the client’s second or third toe.

Clients with pes planus/pronation distortion syndrome, also known as a flexible foot, will exhibit overpronation of the foot where the medial longitudinal arch has fallen and flattened and the forefoot may align slightly outward, which is a sign of a combination of excessive foot eversion and forefoot abduction (Figure 3). With this foot posture, the toes will point slightly outward as opposed to straight ahead. It is then common for clients with pes planus/pronation distortion syndrome to exhibit slight internal rotation of the lower leg (i.e., tibia and fibula) with their knees then being positioned more medially in the frontal plane (i.e., knock-kneed) and their patella possibly pointing slightly inward (Figure 4). The medial displacement of the client’s knees in the frontal plane is known as knee valgus or knee abduction due to the outward angle of the tibia on the distal femur. Therefore, the client’s knees will not line up with their second or third toes but rather their great toe or possibly even more medial to the great toe (Figure 4). Please note that knee valgus is more commonly witnessed in female clients due to their wider pelvic structure and increased quadriceps or Q-angle.

Pes planus/pronation distortion syndrome has been correlated with acute injuries like ankle sprains, calf strains, and knee injuries (e.g., ACL and MCL tears and medial meniscus pathologies) as well as chronic musculoskeletal conditions, such as patellofemoral pain syndrome, anterior and posterior tibialis pathologies, Achilles tendinopathy, plantar fasciitis, hallux valgus (i.e., bunions), and even low back pathologies.

Please note that a static postural assessment is just the beginning of a comprehensive health and fitness assessment. When clients perform dynamic postural assessments, such as the overhead squat assessment, single-leg squat assessment, and gait assessment, signs of pes planus/pronation distortion syndrome will become much more apparent. Therefore, you should only note the presence of pes planus/pronation distortion syndrome if it is obvious in a static standing position.

Lower Crossed Syndrome

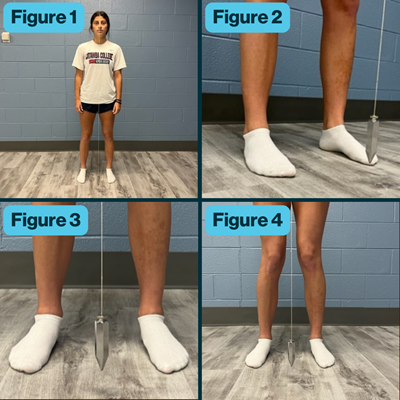

To assess clients for signs of lower crossed syndrome, the fitness professional must assess the client from a lateral view. The plumb bob at the bottom of the plumb line (if used), should line up just anteriorly to the client’s lateral malleolus. Ideally, the plumb line, line in the wall, or imaginary line should be slightly anterior to the middle of the knee joint, slightly posterior or in line with the hip joint, midway through the shoulder joint, and in line with the external auditory meatus of the ear (Figure 5).

To assess clients for signs of lower crossed syndrome, the fitness professional must assess the client from a lateral view. The plumb bob at the bottom of the plumb line (if used), should line up just anteriorly to the client’s lateral malleolus. Ideally, the plumb line, line in the wall, or imaginary line should be slightly anterior to the middle of the knee joint, slightly posterior or in line with the hip joint, midway through the shoulder joint, and in line with the external auditory meatus of the ear (Figure 5).

During a static postural assessment, lower crossed syndrome is characterized by the knee possibly being in a hyperextended position, the hip joint flexed, the pelvis in an excessive anterior pelvic tilt, and the lumbar spine in excessive extension or lordosis (Figure 6). It is important to note that asymptomatic individuals have been shown to have a natural anterior pelvic tilt where their posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) of the ilium is slightly higher than their anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). This slight anterior pelvic tilt allows humans to have a natural inward curve in their lumbar spine, i.e., lordosis. However, if you perceive an excessive anterior pelvic tilt and lordosis, you should note this within your client’s health and fitness assessment datasheet.

Lower crossed syndrome has been primarily correlated with low back pathologies. However, it is not uncommon for a client to exhibit both lower crossed syndrome and pes planus/pronation distortion syndrome. The combination of these two postural distortion syndromes may increase the likelihood of both pain and the musculoskeletal conditions previously mentioned, as well as acute injuries like strained hamstrings or hip adductors. As previously mentioned, when clients perform dynamic postural assessments, such as the overhead squat assessment, gait assessment, and upper body pushing and pulling assessments, signs of lower crossed syndrome will become much more apparent. Therefore, you should only note the presence of lower crossed syndrome if it is obvious in a static standing position.

Upper Crossed Syndrome

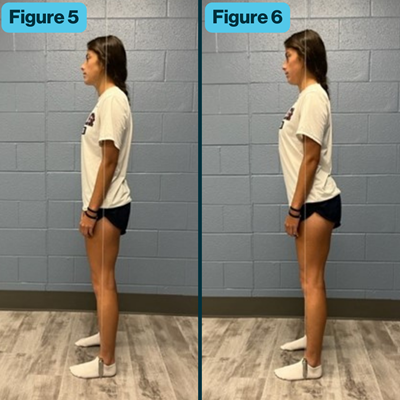

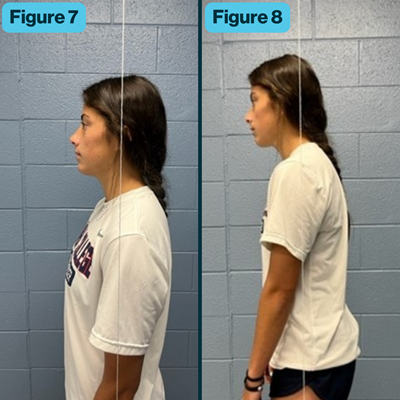

From the lateral view, with an ideal static posture of the thoracic spine, shoulder complex (i.e., shoulder girdle and shoulder joint), and head/neck region, the plumb line, line in the wall, or imaginary line should lie midway through the shoulder joint and be in line with the external auditory meatus of the ear (Figure 7).

From the lateral view, with an ideal static posture of the thoracic spine, shoulder complex (i.e., shoulder girdle and shoulder joint), and head/neck region, the plumb line, line in the wall, or imaginary line should lie midway through the shoulder joint and be in line with the external auditory meatus of the ear (Figure 7).

Clients with upper crossed syndrome will commonly exhibit an excessive kyphotic curve in their thoracic spine, rounded or protracted scapulae with the shoulder joint falling anterior to the line, possibly internally rotated shoulder joints (i.e., arms falling forward and palms of the hands facing backward), and/or the external auditory meatus of the ear lining up anterior to the line, which as often referred to as forward head (Figure 8). Note that some clients may exhibit all of the signs of upper crossed syndrome mentioned above, while other clients may only exhibit one sign (e.g., the client has a normal alignment of the thoracic spine and shoulder complex but exhibits a forward head posture). Therefore, it’s important to make detailed notes in your client’s health and fitness assessment datasheet.

Upper crossed syndrome has been associated with numerous musculoskeletal conditions, specifically chronic conditions. Due to excessive kyphosis and rounded and internally rotated shoulders, clients with upper crossed syndrome may be at risk for conditions such as shoulder impingement, rotator cuff pathologies, biceps tendonitis, and shoulder joint instability. A forward head posture may lead to mid- to upper-back pain, neck pain, thoracic outlet syndrome, temporomandibular disorders, and tension headaches. As previously noted, further dynamic postural assessments may exacerbate signs of upper crossed syndrome. Therefore, the fitness professional should only note the presence of upper crossed syndrome if it is obvious in a static standing position.

Putting All the Pieces Together

Although assessing a client’s static posture is just the beginning of a comprehensive assessment of the human body, it is a key element of a health and fitness assessment. A static postural assessment will assist you in detecting possible muscular imbalances and in developing an individualized exercise program for your client aimed at decreasing the risk of injury and improving performance. For a comprehensive list of static postural deviations and muscular imbalances associated with these deviations, please refer to this resource.

Related content:

Blog | A Fitness Professional’s Introductory Guide to Assessing Static Posture: Part I

Related CEC Courses:

Using Posture to Enhance Movement (1 CEC)

Anatomy of Movement (5 CECs)

Ryan R. Fairall, Ph.D., ACSM-EP, EIM, CSCS, is an assistant professor of exercise science at Catawba College in Salisbury, N.C. He has worked in the fields of health/fitness and sports since the year 2000, has been a certified personal trainer since 2003, and has been an instructor in higher education since 2015. In his free time, Ryan enjoys being physically active — lifting weights, playing sports, kayaking, fishing, going on walks with his female Shih Tzu, Bledsoe, and watching his hometown Philadelphia sports teams, which can be very frustrating at times.