by

Greg Margason

| Mar 06, 2024

As the associate vice president of certification and credentialing at ACSM, one area I am most passionate about is supporting ACSM’s exercise professionals in navigating their career goals. I have had the distinct pleasure of connecting with numerous stakeholders across the spectrum of the exercise profession: students starting their careers in the exercise sciences, professors connecting scientific theories and exercise prescription, employers offering interns their first real-world experiences, and rising professionals trying to find ways to advance in their careers amid growing responsibilities. Earning a certification, while certainly a significant professional milestone, represents just the first step in a lifelong career.

First Things First

Continuing education (CE) — often referred to as “continuing professional development” — is a key element of professional certifications. Professional certification standards from the National Commission of Certifying Agencies and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) require organizations like ACSM to have a time-limited process through which its professionals regularly update their knowledge and skills to maintain a certification in good standing. By participating in CE, certified professionals can demonstrate that they are current with updated professional standards and can meet the changing needs of their clients and patients. Certifying organizations can then provide reasonable assurance to the public that their certified exercise professionals are safe/effective throughout their working career.

Continuing education can take a variety of forms, which provides exercise professionals the flexibility in how and when they want their education to be delivered. From workshops and conference sessions to online on-demand classes and peer-reviewed journals, there are endless ways to meet the learning style and schedule of most exercise professionals.

Beyond Minimum Competence

Beyond maintaining up-to-date current professional standards, certified professionals are encouraged to invest in their career advancement. (This is one among many important differences between an academic degree and a professional certification — once you earn a degree, it’s yours, but most professional certifications require you to continually invest in yourself and your education.) As such, the NCCA grants certification organizations the flexibility to distinguish between initial competence and continuing competence, where initial competence means demonstrating competency in foundational knowledge and skills at the time of certification and continuing competence means both maintaining one’s initial knowledge and skills and gaining new competencies over time. In other words, continuing competence allows certified professionals to not only remain current and relevant in their respective fields but also empowers professionals to advance professionally through specialized training or forge new professional roles within health fitness.

Against the backdrop of the seismic changes the health fitness sector experienced from 2020 onward, successful career advancement requires additional effort from both the exercise professional and the certifying organization. The ACSM Board of Trustees (BOT) and the ACSM Committee on Certification and Registry Boards (CCRB) have taken proactive steps to identify stakeholder concerns and prioritize them in short- and long-term action plans. The BOT has undertaken a comprehensive reimagination of its strategic plan, envisioning a future where lives are extended and enriched through the power of movement. At the same time, the CCRB has revised its mission to expand beyond certification exams and include the lifelong development of its certified professionals. The CCRB’s new mission aims to provide exercise professionals with the latest evidence-based education geared toward early, mid-, and late-stage career professionals with the goals of creating a more agile and resilient workforce and making ACSM a home for certified professional to grow and thrive in their careers.

Career Advancement through Specialty Credentials

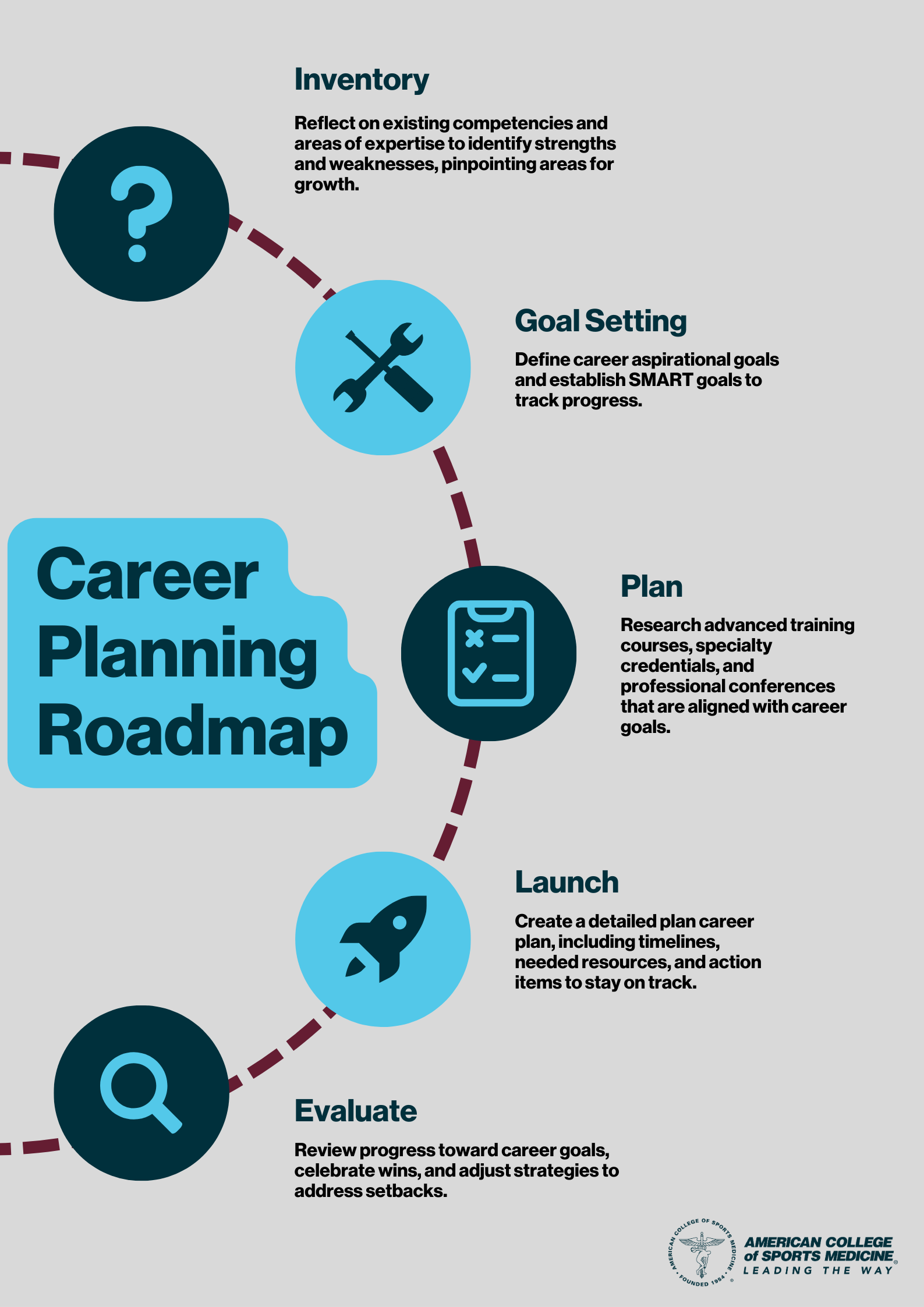

Successful career planning requires self-reflection and intentional goal-setting. This helps professionals develop a process to guide them toward an aspirational goal and a way to pivot in/around obstacles during a career journey. Start by creating an inventory of one’s unique knowledge, skills, experiences and the types of clients served. Identify areas where additional training or education is needed and develop a short- and long-term plan. And, most importantly, take action. With that said, it’s important to know that plans, not matter how meticulous, are never perfect, so exercise professionals should take time to celebrate their wins and, when they encounter roadblocks, take time to adjust the tactics and/or goals as necessary.

Career-Planning

Roadmap

Take Inventory: Reflect on your existing competencies and areas of expertise to identify strengths and weaknesses and pinpoint areas for growth.

Set Goals: Define your career aspirations and develop specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound (SMART) goals to track your progress.

Plan: Research advanced training courses, specialty credentials and professional conferences that would support your career goals.

Launch: Create a detailed career plan, including timelines, needed resources, and action items to stay on track.

Evaluate: Review your progress, celebrate wins, and adjust your strategies to address any setbacks.

(Click the infographic to the right to see it in full resolution.)

ACSM offers a range of specialty credentials for exercise professionals seeking to deepen their expertise and expand their career opportunities. ACSM designed its specialty certificates to expand certificants’ knowledge and skills in their base certification (i.e., ACSM-GEI, ACSM-CPT, ACSM-EP, ACSM-CEP) to work with clients with special considerations; this includes, but is not limited to, cancer survivors, individuals with autism, and those with special considerations (such as youth athletes). For example, the Autism Exercise Specialist certificate equips professionals with the understanding and strategies needed to implement individual or group exercise programs for individuals with autism. Additionally, the Exercise is Medicine® (EIM) Credential teaches exercise professionals how to help individuals with common chronic diseases lead healthier, more active lives, making those with such a credential trusted referral resources for health care providers. ACSM’s specialty credentials enable exercise professionals to extend and enrich lives of their clients and patients through transformative power of movement.

Bringing It Together

Navigating the landscape of CE and career advancement requires a proactive and strategic approach. At a minimum, it is crucial for exercise professionals to stay current with the ongoing changes to professional standards and industry trends. Career exercise pros must also strategically invest in opportunities for personal and professional growth. Developing a career plan helps keep exercise professionals accountable by providing a framework for setting goals, identifying areas for improvement, and tracking/adjusting progress over time. This proactive approach helps ensure exercise professionals achieve long-term success and fulfilling careers.

Learn more about our specialty certifications and certificates:

Francis Neric, MS, MBA currently serves as the associate vice president of certification and credentialing at the American College of Sports Medicine® (ACSM). With professional credentialing experience spanning 16 years, Francis has been instrumental in leading strategic initiatives to enhance the certification, advanced certificate and exam preparation programs to meet the needs of the domestic and international stakeholders of ACSM and the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA). Francis holds an MBA in business management from the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, an M.S. in clinical exercise physiology from California State University, Fullerton, and a B.S. in exercise science from California State University, Long Beach. Francis combines academic and industry knowledge to drive innovation and excellence in the health fitness industry. Francis is a passionate advocate for raising the bar for professionalism in the health fitness industry and expanding opportunities for exercise professionals in health care.